"We have some 2,000 or 2,200 objects that I call the 'red order of battle.'"

Col. Raj Agrawal participates in a change of command ceremony to mark his departure from Mission Delta 2 at Peterson Space Force Base, Colorado. Col. Barry Croker became the new commander of Mission Delta 2 on July 3.

For two years, Col. Raj Agrawal commanded the US military unit responsible for tracking nearly 50,000 human-made objects whipping through space. In this role, he was keeper of the orbital catalog and led teams tasked with discerning whether other countries' satellites, mainly China and Russia, are peaceful or present a military threat to US forces.

This job is becoming more important as the Space Force prepares for the possibility of orbital warfare.

Ars visited with Agrawal in the final weeks of his two-year tour of duty as commander of Mission Delta 2, a military unit at Peterson Space Force Base, Colorado. Mission Delta 2 collects and fuses data from a network of sensors "to identify, characterize, and exploit opportunities and mitigate vulnerabilities" in orbit, according to a Space Force fact sheet.

This involves operating radars and telescopes, analyzing intelligence information, and "mapping the geocentric space terrain" to "deliver a combat-ready common operational picture" to military commanders. Agrawal's job has long existed in one form or another, but the job description is different today. Instead of just keeping up with where things are in space—a job challenging enough—military officials now wrestle with distinguishing which objects might have a nefarious purpose.

From teacher to commander

Agrawal's time at Mission Delta 2 ended on July 3. His next assignment will be as Space Force chair at the National Defense University. This marks a return to education for Agrawal, who served as a Texas schoolteacher for eight years before receiving his commission as an Air Force officer in 2001.

"Teaching is, I think, at the heart of everything I do," Agrawal said.

He taught music and math at Trimble Technical High School, an inner city vocational school in Fort Worth. "Most of my students were in broken homes and unfortunate circumstances," Agrawal said. "I went to church with those kids and those families, and a lot of times, I was the one bringing them home and taking them to school. What was [satisfying] about that was a lot of those students ended up living very fulfilling lives."

Agrawal felt a calling for higher service and signed up to join the Air Force. Given his background in music, he initially auditioned for and was accepted into the Air Force Band. But someone urged him to apply for Officer Candidate School, and Agrawal got in. "I ended up on a very different path."

Agrawal was initially accepted into the ICBM career field, but that changed after the September 11 attacks. "That was a time with anyone with a name like mine had a hard time," he said. "It took a little bit of time to get my security clearance."

Instead, the Air Force assigned him to work in space operations. Agrawal quickly became an instructor in space situational awareness, did a tour at the National Reconnaissance Office, then found himself working at the Pentagon in 2019 as the Defense Department prepared to set up the Space Force as a new military service. Agrawal was tasked with leading a team of 100 people to draft the first Space Force budget.

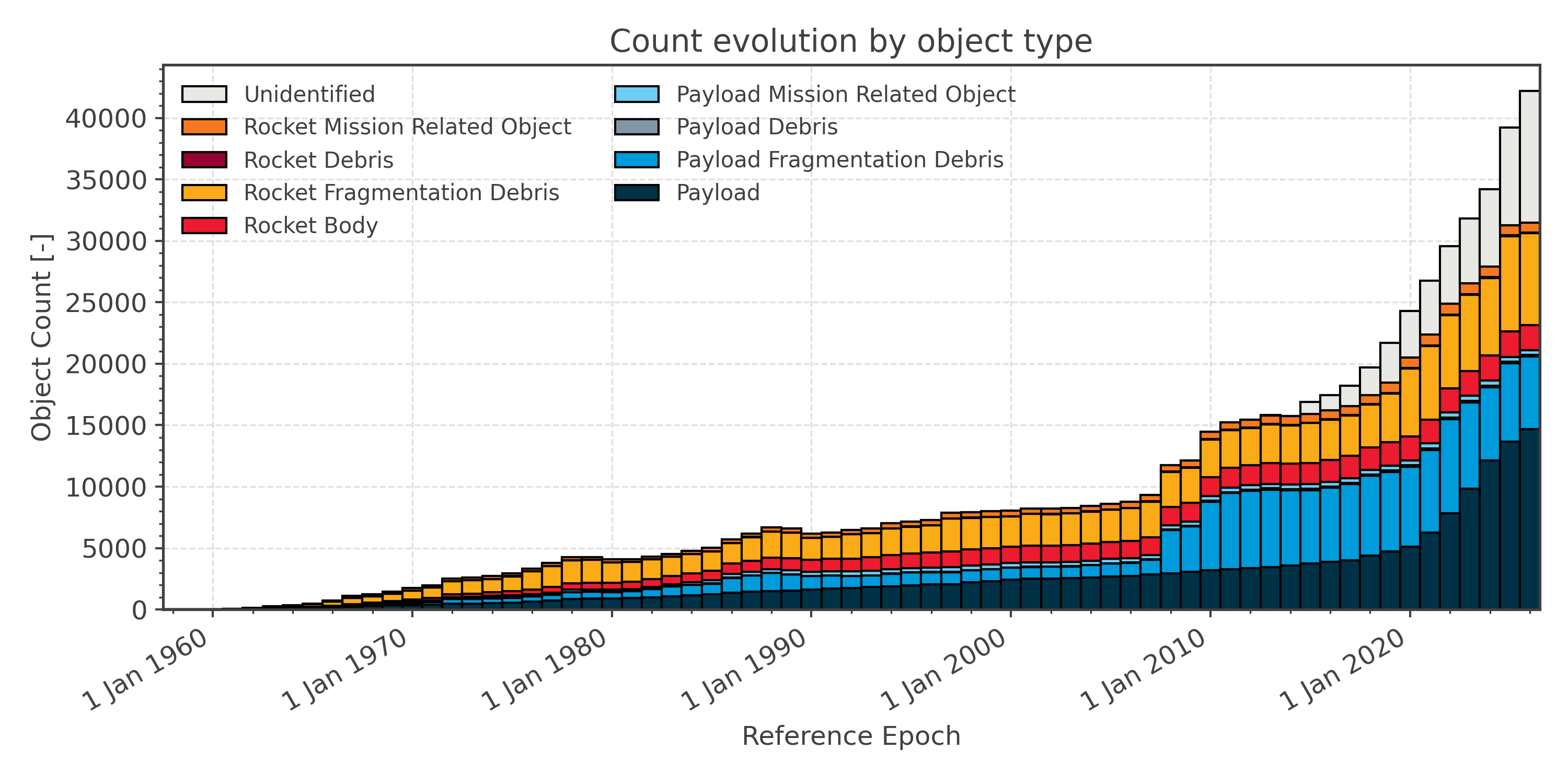

Then, he received the call to report to Peterson Space Force Base to take command of what is now Mission Delta 2, the inheritor of decades of Air Force experience cataloging everything in orbit down to the size of a softball. The catalog was stable and predictable, lingering below 10,000 trackable objects until 2007. That's when China tested an anti-satellite missile, shattering an old Chinese spacecraft into more than 3,500 pieces large enough to be routinely detected by the US military's Space Surveillance Network.

This graph from the European Space Agency shows the growing number of trackable objects in orbit. Credit: European Space Agency

Two years later, an Iridium communications satellite collided with a defunct Russian spacecraft, adding thousands more debris fragments to low-Earth orbit. A rapid uptick in the pace of launches since then has added to the problem, further congesting busy orbital traffic lanes a hundred miles above the Earth. Today, the orbital catalog numbers roughly 48,000 objects.

"This compiled data, known as the space catalog, is distributed across the military, intelligence community, commercial space entities, and to the public, free of charge," officials wrote in a fact sheet describing Mission Delta 2's role at Space Operations Command. Deltas are Space Force military units roughly equivalent to a wing or group command in the Air Force.

The room where it happens

The good news is that the US military is getting better at tracking things in space. A network of modern radars and telescopes on the ground and in space can now spot objects as small as a golf ball. Space is big, but these objects routinely pass close to one another. At speeds of nearly 5 miles per second, an impact will be catastrophic.

But there's a new problem. Today, the US military must not only screen for accidental collisions but also guard against an attack on US satellites in orbit. Space is militarized, a fact illustrated by growing fleets of satellites—primarily American, Chinese, and Russian—capable of approaching another country's assets in orbit, and in some cases, disable or destroy them. This has raised fears at the Pentagon that an adversary could take out US satellites critical for missile warning, navigation, and communications, with severe consequences impacting military operations and daily civilian life.

This new reality compelled the creation of the Space Force in 2019, beginning a yearslong process of migrating existing Air Force units into the new service. Now, the Pentagon is posturing for orbital warfare by investing in new technologies and reorganizing the military's command structure.

Today, the Space Force is responsible for predicting when objects in orbit will come close to one another. This is called a conjunction in the parlance of orbital mechanics. The US military routinely issues conjunction warnings to commercial and foreign satellite operators to give them an opportunity to move their satellites out of harm's way. These notices also go to NASA if there's a chance of a close call with the International Space Station (ISS).

The first Trump administration approved a new policy to transfer responsibility for these collision warnings to the Department of Commerce, allowing the military to focus on national security objectives.

But the White House's budget request for next year would cancel the Commerce Department's initiative to take over collision warnings. Our discussion with Agrawal occurred before the details of the White House budget were made public last month, and his comments reflect official Space Force policy at the time of the interview. "In uniform, we align to policy," Agrawal wrote on his LinkedIn account. "We inform policy decisions, but once they’re made, we align our support accordingly."

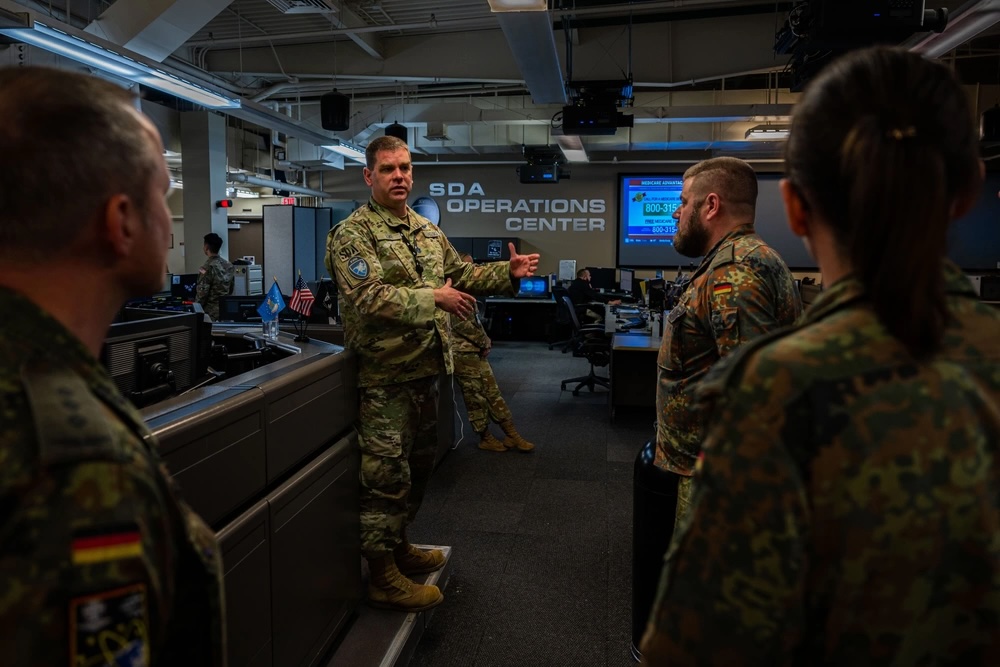

US Space Force officials show the 18th Space Defense Squadron's operations floor to officials from the German Space Situational Awareness Centre during an "Operator Exchange" event at Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, on April 7, 2022. Credit: US Space Force/Tech. Sgt. Luke Kitterman

Since our interview, analysts have also noticed an uptick in interesting Russian activity in space and tracked a suspected Chinese satellite refueling mission in geosynchronous orbit.

Let's rewind the tape to 2007, the time of China's game-changing anti-satellite test. Gen. Chance Saltzman, today the Space Force's Chief of Space Operations, was a lieutenant colonel in command of the Air Force's 614th Space Operations Squadron at the time. He was on duty when Air Force operators first realized China had tested an anti-satellite missile. Saltzman has called the moment a "pivot point" in space operations. "For those of us that are neck-deep in the business, we did have to think differently from that day on," Saltzman said in 2023.

Agrawal was in the room, too. "I was on the crew that needed to count the pieces," he told Ars. "I didn’t know the significance of what was happening until after many years, but the Chinese had clearly changed the nature of the space environment."

The 2007 anti-satellite test also clearly changed the trajectory of Agrawal's career. We present part of our discussion with Agrawal below, and we'll share the rest of the conversation tomorrow. The text has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Ars: The Space Force's role in monitoring activities in space has changed a lot in the last few years. Can you tell me about these changes, and what's the difference between what you used to call Space Situational Awareness, and what is now called Space Domain Awareness?

Agrawal: We just finished our fifth year as a Space Force, so as a result of standing up a military service focused on space, we shifted our activities to focus on what the joint force requires for combat space power. We've been doing space operations for going on seven decades. I think a lot of folks think that it was a rebranding, as opposed to a different focus for space operations, and it couldn’t be further from the truth. Compared to Space Domain Awareness (SDA), Space Situational Awareness (SSA) is kind of the knowledge we produce with all these sensors, and anybody can do space situational awareness. You have academia doing that. You've got commercial, international partners, and so on. But Space Domain Awareness, Gen. [John "Jay"] Raymond coined the term a couple years before we stood up the Space Force, and he was trying to get after, how do we create a domain focused on operational outcomes? That's all we could say at the time. We couldn't say war-fighting domain at the time because of the way of our policy, but our policy shifted to being able to talk about space as a place where, not that we want to wage war, but that we can achieve objectives, and do that with military objectives in mind.

We used to talk about detect, characterize, attribute, predict. And then Gen. [Chance] Saltzman added target onto the construct for Space Domain Awareness, so that we're very much in the conversation of what it means to do a space-enabled attack and being able to achieve objectives in, from, and to space, and using Space Domain Awareness as a vehicle to do those things. So, with Mission Delta 2, what he did is he took the sustainment part of acquisition, software development, cyber defense, intelligence related to Space Domain Awareness, and then all the things that we were doing in Space Domain Awareness already, put all that together under one command ... and called us Mission Delta 2. So, the 18th Space Defense Squadron ... that used to kind of be the center of the world for Space Domain Awareness, maybe the only unit that you could say was really doing SDA, where everyone else was kind of doing SSA. When I came into command a couple years ago, and we face now a real threat to having space superiority in the space domain, I disaggregated what we were doing just in the 18th and spread out through a couple of other units ... So, that way everyone's got kind of majors and minors, but we can quickly move a mission in case we get tested in terms of cyber defense or other kinds of vulnerabilities.

This multi-exposure image depicts a satellite-filled sky over Alberta. Credit: Alan Dyer/VWPics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

We can't see the space domain, so it's not like the air domain and sea domain and land domain, where you can kind of see where everything is, and you might have radars, but ultimately it's a human that's verifying whether or not a target or a threat is where it is. For the space domain, we’re doing all that through radars, telescopes, and computers, so the reality we create for everyone is essentially their reality. So, if there's a gap, if there's a delay, if there are some signs that we can't see, that reality is what is created by us, and that is effectively the reality for everyone else, even if there is some other version of reality in space. So, we're getting better and better at fielding capability to see the complexity, the number of objects, and then translating that into what's useful for us—because we don't need to see everything all the time—but what's useful for us for military operations to achieve military objectives, and so we've shifted our focus just to that.

We're trying to get to where commercial spaceflight safety is managed by the Office of Space Commerce, so they're training side by side with us to kind of offload that mission and take that on. We're doing up to a million notifications a day for conjunction assessments, sometimes as low as 600,000. But last year, we did 263 million conjunction notifications. So, we want to get to where the authorities are rightly lined, where civil or commercial notifications are done by an organization that's not focused on joint war-fighting, and we focus on the things that we want to focus on.

Ars: Thank you for that overview. It helps me see the canvas for everything else we're going to talk about. So, today, you’re not only tracking new satellites coming over the horizon from a recent launch or watching out for possible collisions, you’re now trying to see where things are going in space and maybe even try to determine intent, right?

Agrawal: Yeah, so the integrated mission delta has helped us have intel analysts and professionals as part of our formation. Their mission is SDA as much as ours is, but they're using an intel lens. They're looking at predictive intelligence, right? I don't want to give away tradecraft, but what they're focused on is not necessarily where a thing is. It used to be that all we cared about was position and vector, right? As long as you knew an object’s position and the direction they were going, you knew their orbit. You had predictive understanding of what their element set would be, and you only had to do sampling to get a sense of ... Is it kind of where we thought it was going to be? ... If it was far enough off of its element set, then we would put more energy, more sampling of that particular object, and then effectively re-catalog it.

Now, it's a different model. We're looking at state vectors, and we're looking at anticipatory modeling, where we have some 2,000 or 2,200 objects that I call the "red order of battle"—that are high-interest objects that we anticipate will do things that are not predicted, that are not element set in nature, but that will follow some type of national interest. So, our intel apparatus gets after what things could potentially be a risk, and what things to continue to understand better, and what things we have to be ready to hold at risk. All of that's happening through all the organizations, certainly within this delta, but in partnership and in support of other capabilities and deltas that are getting after their parts of space superiority.

Hostile or friendly?

Ars: Can you give some examples of these red order of battle objects?

Agrawal: I think you know about Shijian-20 (a "tech demo" satellite that has evaded inspection by US satellites) and Shijian-24C (which the Space Force says demonstrated "dogfighting" in space), things that are advertised as scientific in nature, but clearly demonstrate capability that is not friendly, and certainly are behaving in ways that are unprofessional. In any other domain, we would consider them hostile, but in space, we try to be a lot more nuanced in terms of how we characterize behavior, but still, when something's behaving in a way that isn't pre-planned, isn't pre-coordinated, and potentially causes hazard, harm, or contest with friendly forces, we now get in a situation where we have to talk about is that behavior hostile or not? Is that escalatory or not? Space Command is charged with those authorities, so they work through the legal apparatus in terms of what the definition of a hostile act is and when something behaves in a way that we consider to be of national security interest.

We present all the capability to be able to do all that, and we have to be as cognizant on the service side as the combatant commanders are, so that our intel analysts are informing the forces and the training resources to be able to anticipate the behavior. We're not simply recognizing it when it happens, but studying nations in the way they behave in all the other domains, in the way that they set policy, in the way that they challenge norms in other international arenas like the UN and various treaties, and so on. The biggest predictor, for us, of hazardous behaviors is when nations don't coordinate with the international community on activities that are going to occur—launches, maneuvers, and fielding of large constellations, megaconstellations.

Starlink satellites. Credit: Starlink

There are nearly 8,000 Starlink satellites in orbit today. SpaceX adds dozens of satellites to the constellation each week. Credit: SpaceX

As you know, we work very closely with Starlink, and they're very, very responsible. They coordinate and flight plan. They use the kind of things that other constellations are starting to use ... changes in those elsets (element sets), for lack of a better term, state vectors, we're on top of that. We're pre-coordinating that. We’re doing that weeks or months in advance. We're doing that in real-time in cooperation with these organizations to make sure that space remains safe, secure, accessible, profitable even, for industry. When you have nations, where they're launching over their population, where they're creating uncertainty for the rest of the world, there's nothing else we can do with it other than treat that as potentially hostile behavior. So, it does take a lot more of our resources, a lot more of our interest, and it puts [us] in a situation where we're posturing the whole joint force to have to deal with that kind of uncertainty, as opposed to cooperative launches with international partners, with allies, with commercial, civil, and academia, where we're doing that as friends, and we're doing that in cooperation. If something goes wrong, we're handling that as friends, and we're not having to involve the rest of the security apparatus to get after that problem.

Ars: You mentioned that SpaceX shares Starlink orbit information with your team. Is it the same story with Amazon for the Kuiper constellation?

Agrawal: Yeah, it is. The good thing is that all the US and allied commercial entities, so far, have been super cooperative with Mission Delta 2 in particular, to be able to plan out, to talk about challenges, to even change the way they do business, learning more about what we are asking of them in order to be safe. The Office of Space Commerce, obviously, is now in that conversation as well. They're learning that trade and ideally taking on more of that responsibility. Certainly, the evolution of technology has helped quite a bit, where you have launches that are self-monitored, that are able to maintain their own safety, as opposed to requiring an entire apparatus of what was the US Air Force often having to expend a tremendous amount of resources to provide for the safety of any launch. Now, technology has gotten to a point where a lot of that is self-monitored, self-reported, and you'll see commercial entities blow up their own rockets no matter what's onboard if they see that it's going to cause harm to a population, and so on. So, yeah, we’re getting a lot of cooperation from other nations, allies, partners, close friends that are also sharing and cooperating in the interest of making sure that space remains sustainable and secure.

“We’ve made ourselves responsible”

Ars: One of the great ironies is that after you figure out the positions and tracks of Chinese or Russian satellites or constellations, you’re giving that data right back to them in the form of conjunction and collision notices, right?

Agrawal: We’ve made ourselves responsible. I don't know that there's any organization holding us accountable to that. We believe it's in our interests, in the US's interests, to provide for a safe, accessible, secure space domain. So, whatever we can do to help other nations also be safe, we're doing it certainly for their sake, but we're doing it as much for our sake, too. We want the space domain to be safe and predictable. We do have an apparatus set up in partnership with the State Department, and with a tremendous amount of oversight from the State Department, and through US Space Command to provide for spaceflight safety notifications to China and Russia. We send notes directly to offices within those nations. Most of the time they don't respond. Russia, I don't recall, hasn't responded at all in the past couple of years. China has responded a couple of times to those notifications. And we hope that, through small measures like that, we can demonstrate our commitment to getting to a predictable and safe space environment.

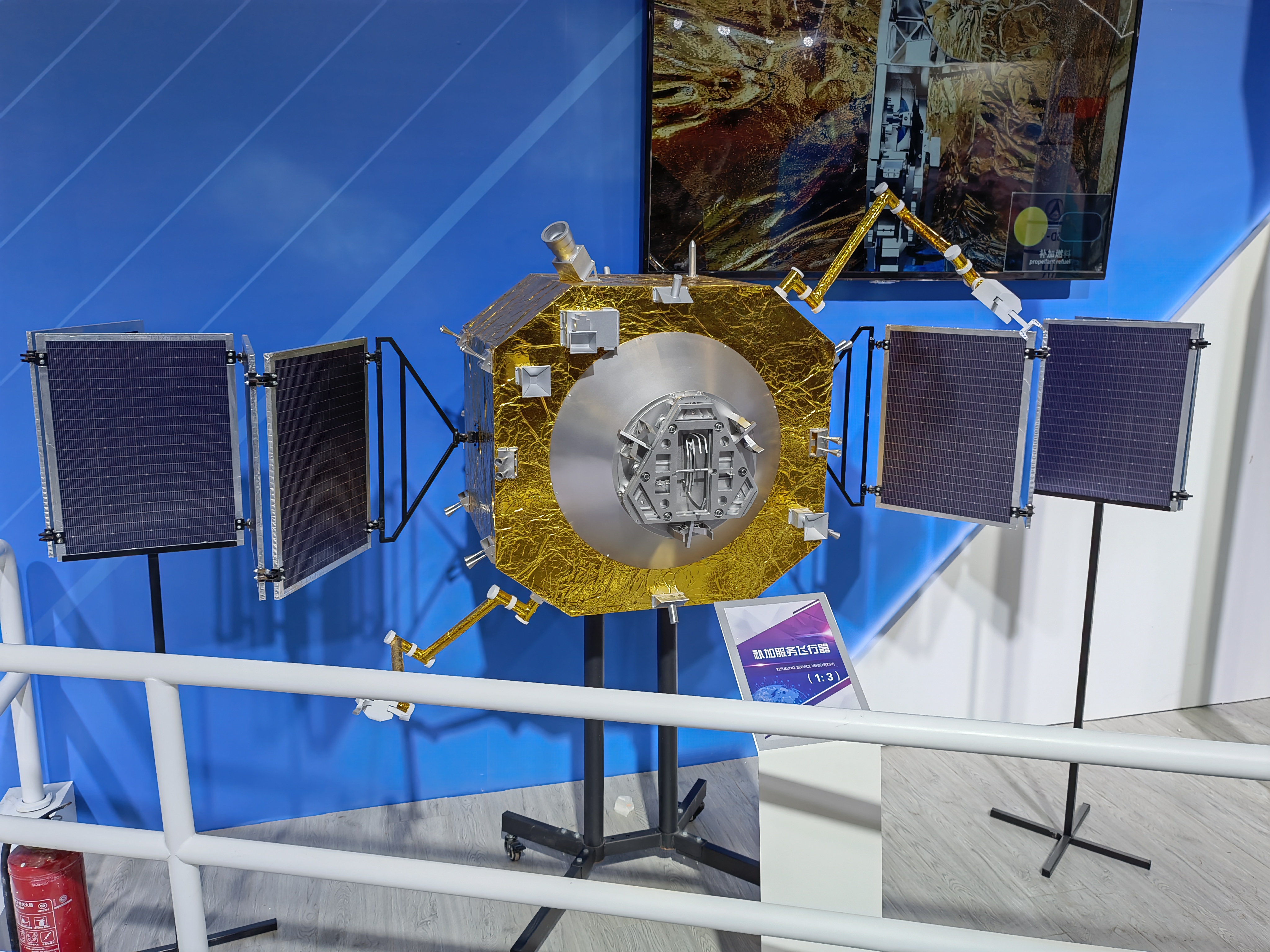

A model of a Chinese satellite refueling spacecraft on display during the 13th China International Aviation and Aerospace Exhibition on October 1, 2021, in Zhuhai, Guangdong Province of China. Credit: Photo by VCG/VCG via Getty Images

Ars: What does China say in response to these notices?

Agrawal: Most of the time it's copy or acknowledged. I can only recall two instances where they've responded. But we did see some hope earlier this year and last year, where they wanted to open up technical exchanges with us and some of their [experts] to talk about spaceflight safety, and what measures they could take to open up those kinds of conversations, and what they could do to get a more secure, safer pace of operations. That, at some point, got delayed because of the holiday that they were going through, and then those conversations just halted, or at least progress on getting those conversations going halted. But we hope that there'll be an opportunity again in the future where they will open up those doors again and have those kinds of conversations because, again, transparency will get us to a place where we can be predictable, and we can all benefit from orbital regimes, as opposed to using them exploitively. LEO is just one of those places where you're not going to hide activity there, so you just are creating risk, uncertainty, and potential escalation by launching into LEO and not communicating throughout that whole process.

Ars: Do you have any numbers on how many of these conjunction notices go to China and Russia? I’m just trying to get an idea of what proportion go to potential adversaries.

Agrawal: A lot. I don't know the degree of how many thousands go to them, but on a regular basis, I'm dealing with debris notifications from Russian and Chinese ASAT (anti-satellite) testing. That has put the ISS at risk a number of times. We've had maneuvers occur in recent history as a result of Chinese rocket body debris. Debris can’t maneuver, and unfortunately, we've gotten into situations with particularly those two nations that talk about wanting to have safer operations, but continue to conduct debris-causing tests. We're going to be dealing with that for generations, and we are going to have to design capability to maneuver around those debris clouds as just a function of operating in space. So, we’ve got to get to a point where we’re not doing that kind of testing in orbit.

Ars: Would it be accurate to say you send these notices to China and Russia daily?

Agrawal: Yeah, absolutely. That’s accurate. These debris clouds are in LEO, so as you can imagine, as those debris clouds go around the Earth every 90 minutes, we're dealing with conjunctions. There are some parts of orbits that are just unusable as a result of that unsafe ASAT test.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·