Nvidia’s RTX 6000D was never going to be a hero product. Built specifically for the Chinese market to navigate U.S. export restrictions, it has a constrained design: a GDDR-based Blackwell GPU with no NVLink, targeting AI inference instead of full-scale training.

Two procurement sources speaking to the South China Morning Post say that demand is tepid and the chip’s value proposition is “expensive for what it does.” And that’s before you factor in the uncomfortable comparison to Nvidia’s own RTX 5090, the flagship gaming GPU that’s officially banned from China but widely available through grey-market channels. By some measure, that consumer card not only costs half as much but outperforms the 6000D in the same inference tasks Nvidia designed its export-safe silicon to run.

Blackwell sans bandwidth

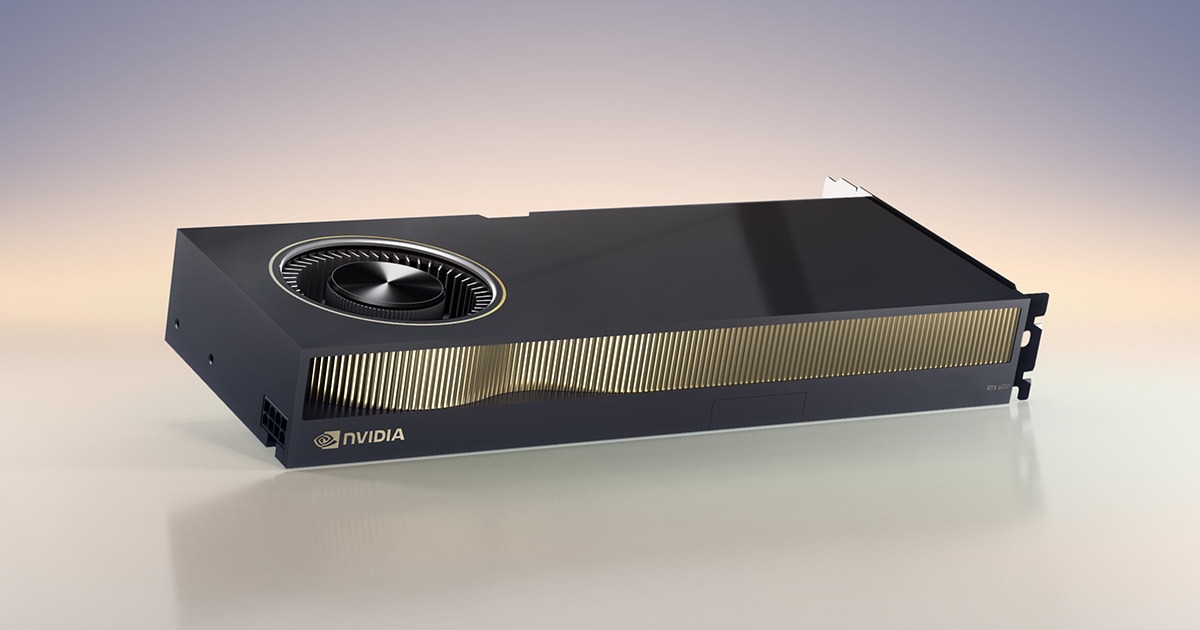

Nvidia hasn’t published formal specifications for the RTX 6000D, but multiple sources indicate it uses Blackwell architecture with conventional GDDR memory, and delivers around 1,398 GB/s of bandwidth — just under the 1.4 TB/s export limit. There are strong indications that it avoids HBM and high‑bandwidth interconnect packaging, suggesting simpler die structures and likely dependence on PCIe or external NICs, rather than NVLink.

In other words, the 6000D is a PCIe workstation card that looks a lot like the RTX 6000 Blackwell or a tweaked 5090, just with a different name and a dramatically higher price tag. But rather than specs, the core issue is what happens when you try to scale it.

Without NVLink, the 6000D may rely on PCIe or external NICs like ConnectX to communicate between GPUs. That puts it at an immediate disadvantage in large-model inference workloads. A 70B-parameter model at FP16 can easily require 140 GB or more just for weights. Even INT8 quantization struggles to fit under 50 GB once you add the KV cache, meaning that you’ll often need two or more GPUs just to serve a single model replica. At that point, GPU-to-GPU comms becomes the bottleneck.

PCIe 4.0 x16 delivers around 64 GB/s of bandwidth. Meanwhile, NVLink 5.0 is closer to 900 GB/s. Nvidia’s own documentation recommends keeping tensor parallelism inside the NVLink domain for exactly this reason — collective operations like all-reduce and activation exchange are latency-sensitive. Try doing that over PCIe or even 800Gbps Ethernet, and step time balloons. Add more 6000Ds to the cluster, and you can imagine how the payoff in throughput starts to collapse. From a buyer's perspective, what’s the point of doing that when you can do better with alternative hardware?

Grey-market swarm

The RTX 6000D retailed in China for around $7,000 (¥50,000). That’s not far off the amount you might expect to pay for a lower-end HBM-based GPU like the H20, not a GDDR card with no NVLink. And unlike the H20, it’s not even pretending to be a training-class GPU.

Now compare that to what’s available unofficially. Grey-market RTX 5090s, which were designed for gamers but blessed with Nvidia’s full Blackwell silicon, are trading for as little as $3,500 (¥25,000). Some are even being resold in blower-style enclosures with expanded VRAM of up to 80GB or even 128GB in modded units. Despite being technically banned under U.S. export rules, they’re everywhere. And they perform.

So, why choose the 6000D when you can get a more powerful grey-market part without any issues? From a throughput-per-yuan perspective, the grey-market 5090 swarm makes the 6000D look like a bad joke. And with better options potentially being just over the horizon, why would Chinese buyers want to spend money on the 6000D at all?

A domestic market right around the corner?

A big part of the 6000D’s lackluster reception is circumstantial. Chinese buyers were still waiting on shipments of Nvidia’s sanctioned H20, an HBM-based Hopper GPU approved for export in July but still stuck in limbo. It’s the chip many hyperscalers wanted for high-density inference, but the latest news of China's Nvidia ban calls into question whether those orders will even be fulfilled.

At the same time, there was a hope that the B30A — a more powerful Blackwell part designed for training — would win approval for sale, too. However, with the new ban on acquiring Nvidia chips, this seems more unlikely than ever. The B30A was reportedly equipped with 144 GB of HBM3E and NVLink support, delivering up to six times the performance of the H20 for only double the price.

As evidenced by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC)'s latest actions, the country is clearly moving beyond reliance on Nvidia chips. There’s a deeper shift underway. China is pushing hard for domestic AI hardware adoption, mandating that state-backed clouds procure at least 50% of their AI accelerators from Chinese vendors. Huawei’s Ascend, Biren’s CloudMatrix, and Cambricon’s NPU lines are all on the table. So is CANN: Huawei’s CUDA alternative that just went fully open source.

This (in theory) allows developers to move workloads away from Nvidia and toward Ascend, but the transition has been rocky. Chinese LLM lab DeepSeek notoriously scrapped plans to train its next model on Ascend NPUs, much to the disdain of the Chinese government, citing unstable performance and poor chip-to-chip communication.

For now, that leaves China’s major clouds effectively locked into CUDA. But the political and strategic pressure to break free is building. From China's perspective, there are too few advantages to justify doubling down on Nvidia’s ecosystem, which would be terminally behind Western counterparts, if export control rules continued.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News to get our up-to-date news, analysis, and reviews in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button.

1 month ago

8

1 month ago

8

English (US) ·

English (US) ·