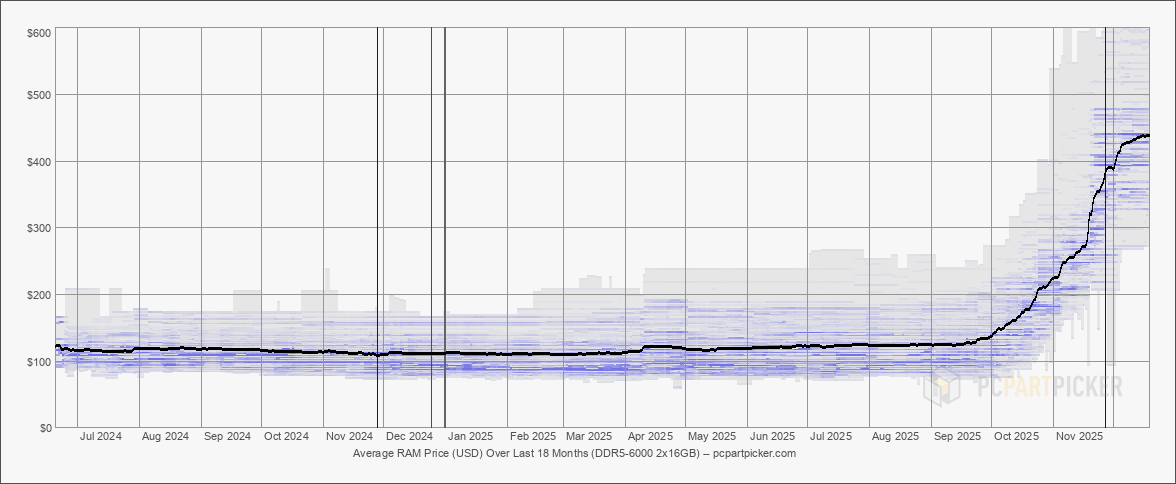

As we detailed in October, the memory and storage markets were expected to face significant supply constraints. In the months following, DDR5 prices have skyrocketed. Kits that had sold comfortably below $100 months earlier were surging into the hundreds by early December. CyberPowerPC, one of the largest system builders in North America, warned in November that contract DRAM prices had jumped 500% since early October, while another report indicated that they had risen 171.8% year over year.

The disruption is being driven not by demand from gamers or device makers, but by artificial intelligence. Specifically, by the way hyperscalers are soaking up wafer starts and advanced packaging lines for high-bandwidth memory (HBM) used in AI accelerators.

The consequence is that anyone or anything that’s not part of that ecosystem — PC builders, laptop OEMs, and even phone makers — is fighting over the scraps of a shrinking pool of commodity DRAM. And with new fabs still years from coming online, the shortage is expected to last well into the second half of the decade.

RAM kits up 2-4x in a quarter

The most visible impact can be seen with retailers. A Corsair Vengeance DDR5-6000 32GB (2x16GB) cost $134.99 in September before reaching more than $420 in early December. G.Skill, TeamGroup, and Kingston all adjusted channel pricing by double digits across Q3, citing tightening availability.

That translated to a whopping 2-4x price swing for enthusiasts buying RAM, depending on capacity and bin. The G. Skill Trident Z5 Neo RGB DDR5-6000, our tried-and-tested best RAM for gaming, is now only available via third-party sellers through Amazon, with 64GB kits attracting prices beyond $500, with one seller listing them for a whopping $881.87 as of December 18.

Suppliers and distributors have sharply tightened allocation of DDR5 memory, with some channel partners reporting severely limited quotes and rollovers on orders as capacity is diverted to AI-driven demand. Reports from Taiwan and broader market tracking show memory modules selling out or being bundled to secure placement, indicating that mainstream buyers are being deprioritized.

That squeeze quickly filtered into GPUs, where memory is a major cost driver. AMD board partners raised card prices by around $10 per 8GB of VRAM starting in November. A rumor suggests AMD could increase Radeon RX graphics card prices with 8 GB models up by about $20 and 16 GB models up by about $40 in response to climbing GDDR6 spot prices and memory costs. SSD pricing has also reversed direction. 2TB Gen 4 NVMe drives that had been available for $80 in the summer were back at $130 by November. Contract pricing on NAND rose 60% in November, and module-level spot prices followed.

Framework was forced to increase its pricing on the DDR5 memory configurable in Framework Laptop DIY Edition orders by 50% in response to “substantially higher costs” they are facing from suppliers and distributors. Meanwhile, Dell and HP have both flagged component pricing, with HP’s CEO stating that memory costs in particular were affecting margin on consumer systems and Dell COO Jeff Clarke saying he’s “never seen memory-chip costs rise this fast.” Raspberry Pi also raised prices on its 4GB and 8GB boards, citing supply constraints on LPDDR4X.

Starving the market

All this is not being caused by insufficient demand for DDR5, but by wafer and packaging capacity being redirected to high-margin, high-volume AI parts. High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) is the main pressure point.

HBM differs from conventional DRAM in both structure and cost. Instead of planar dies mounted on PCBs, HBM stacks multiple DRAM dies vertically, linked with through-silicon vias (TSVs), and mounts them on an interposer alongside compute logic. These stacks offer enormous bandwidth and proximity advantages for AI accelerators, but they are incredibly expensive in terms of materials, tooling requirements, and especially wafer area.

Each gigabyte of HBM consumes roughly three times the wafer capacity of DDR5. That reflects both yield loss from stacking and the fact that many DRAM dies in HBM stacks are smaller or binned lower than equivalent RAM sticks. The TSV process and wafer thinning introduce additional steps that lengthen production cycles, leading to a catch-22 situation that, even when yields are strong, means the vertical integration of HBM requires advanced packaging lines that remain globally scarce.

SK hynix, the largest supplier of HBM to Nvidia, has told investors that its advanced packaging lines are at capacity through 2026. Micron, which supplies HBM3E to Nvidia and other U.S. clients, is in a similar position. Samsung has HBM capacity reserved through its Foundry and Memory business lines for tier-1 cloud clients. These lines are not interchangeable with conventional DRAM; tools, masks, and equipment for HBM production occupy space that would otherwise produce DDR5 or LPDDR5.

With wafer starts flat and packaging lines locked, every wafer pushed into HBM removes capacity from commodity DRAM and NAND. And the volume committed to AI is enormous.

The Stargate effect

In July, OpenAI and Microsoft finalized plans for Project Stargate, a multi-site hyperscale AI infrastructure program, with Samsung and SK hynix together committing to up to 900,000 DRAM wafer starts per month to support the buildout “at an accelerated capacity,” according to OpenAI.

That deal alone represents roughly 35-40% of global DRAM wafer capacity. The wafers will be used not just for HBM stacks, but for LPDDR and ECC DRAM used in adjacent server memory. Nvidia has its own multi-year agreements in place, reportedly accounting for the majority of SK hynix's HBM output through 2026. These allocations are inflexible, with contracts fixed, volumes tiered, and, in many cases, wafers fronted at favorable prices in exchange for capacity guarantees.

Naturally, memory vendors are reaping the rewards. Micron posted a record $11.3 billion quarter in Q4 2025, driven by HBM and enterprise DRAM margins. It subsequently announced plans to exit the Crucial consumer brand by early 2026. Executives stated that winding down Crucial would free up wafer supply for strategic accounts. “The AI-driven growth in the data center has led to a surge in demand for memory and storage. Micron has made the difficult decision to exit the Crucial consumer business... to improve supply and support for our larger, strategic customers in faster-growing segments,” said Sumit Sadana, EVP and Chief Business Officer.

Meanwhile, Samsung has raised its memory chip prices by up to 60% since September, driven almost entirely by the high demand for building new AI-focused data centers.

No new fabs until 2027

Memory makers are responding to surging demand by building new fabs, but the leadtime on greenfield facilities is long, and — of course — virtually all capex is going to go to HBM lines first, because that’s where the money is. Among the most notable investments is Micron’s $9.6 billion Hiroshima HBM facility, announced in partnership with the Japanese government. Construction of this fab is expected to begin around May 2026, with its first output expected in 2028.

Samsung is also committing billions in investments to new DRAM capacity in Pyeongtaek and Taylor, Texas. These sites will include HBM packaging and DRAM wafer lines, but company executives have cautioned that HBM and high-margin enterprise DRAM will receive priority through 2027. The company recently accelerated Phase 4 of its Pyeongtaek expansion in a renewed effort to reclaim leadership in the AI memory space. As for SK hynix, it’s expanding in Icheon — where it was the first memory maker to assemble ASML’s High-NA EUV lithography system — and Cheongju, with new DRAM output slated for 2026-2027.

Unfortunately, there’s no sign of the DRAM supply shortfall easing up before 2027. TrendForce has cautioned time and time again that capacity growth is limited relative to demand as AI and server requirements absorb a disproportionate share of wafer starts and production resources, and its pricing outlook shows DRAM contract rates continuing to rise through 2026 with constrained supply conditions. A leaked SK hynix internal analysis forecasts PC DRAM supply trailing demand until at least late 2028, and general industry consensus is that meaningful relief for DDR5 and LPDDR5 supply — at prices suitable for consumer SKUs — will not come until 2028 or 2029 at the earliest.

The situation is similar for NAND, with wafer investment having lagged since the 2022 price collapse. Most new NAND lines being built now are intended for enterprise SSDs or embedded memory for AI accelerators; client SSDs will see higher costs and tighter supply through 2026.

Consumers are now an afterthought

The effects of this reallocation are already locked into the next generation of consumer hardware, because memory decisions are made years in advance. Laptop platforms shipping in 2026 and 2027 are being finalized now, at a moment when DRAM and NAND supply are both constrained and volatile. That will have consequences that go beyond pricing.

Memory configurations that require large, predictable allocations of DRAM are riskier in a market where suppliers are prioritizing AI contracts and spot pricing can move sharply month to month. These conditions favor fewer SKUs and longer reuse of validated configurations rather than aggressive spec increases. Meanwhile, DDR4, which was expected to fade out quickly after DDR5 adoption ramped, is now likely to persist far longer in entry-level and midrange systems simply because its supply chain is more stable.

GPUs are in a similar bind. GDDR6 and GDDR6X, while not interchangeable with HBM, compete for wafer capacity and backend resources at the same suppliers. That makes large VRAM increases expensive at exactly the moment when software requirements are rising. This won’t necessarily mean fewer GPUs, but it could lead to slower movement at the top end of memory configurations, with vendors prioritizing yield and availability over aggressive capacity scaling.

NAND is under comparable pressure as investment in new client-focused capacity slowed down after oversupply and subsequent pricing collapse in 2022. What capacity is coming online is disproportionately aimed at enterprise SSDs and embedded storage tied to accelerators, where margins are higher, and contracts are longer. That leaves consumer SSDs exposed to price swings and supply tightening, particularly at higher capacities, even as PCIe generations continue to advance.

The problem is that none of these pressures are transient shocks that can clear in a quarter or two. The fabs that would meaningfully expand DRAM and NAND supply are not scheduled to come online until 2027 at the earliest, and even then, priority will remain with HBM and enterprise products. Consumer markets are now an afterthought among memory makers and, given the current state of AI, it’s difficult to see that changing.

6 hours ago

7

6 hours ago

7

English (US) ·

English (US) ·