For much of the past few years, U.S. export controls on advanced AI chips have been justified publicly as a matter of urgency. Policymakers warned that Chinese chipmakers, backed by massive state support and forced into self-reliance, were on the verge of closing the gap with Nvidia in AI hardware. That fear has shaped decisions in Washington, including recent efforts to loosen restrictions on certain Nvidia silicon bound for China.

Now, a new report from the Council on Foreign Relations paints a very different picture. Based on performance data, manufacturing constraints at China’s leading foundry, and realistic production volume estimates, the analysis concludes that Huawei’s AI chip capabilities lag behind Nvidia’s by a wide margin, and that the gap is not narrowing. Indeed, by several measures, it is accelerating.

The report’s findings are especially significant because they directly address U.S. AI policy. If Huawei cannot plausibly catch Nvidia on AI hardware in the medium term, the rationale for relaxing export controls weakens. The question is not whether China is investing heavily in AI silicon. It clearly is. The question is whether those investments are translating into competitive hardware at scale. Right now, this report suggests they are not.

Huawei stuck several generations behind

Huawei’s flagship AI accelerators come from its Ascend line, most recently the Ascend 910C. On paper, the 910C is impressive. It is a large, power-hungry accelerator aimed squarely at data center AI training and inference. In practice, however, its performance ceiling is far below Nvidia’s current generation.

The CFR analysis estimates that the Ascend 910C delivers roughly 60% of the inference performance of Nvidia’s H100 under comparable conditions. That comparison already favors Huawei because Nvidia has moved beyond H100. The H200, which entered volume shipments in 2024 and was recently re-cleared for export to China, substantially increases memory capacity and bandwidth, while Nvidia’s Blackwell generation pushes further still.

Process technology is a major part of the problem. Huawei no longer has access to TSMC and must rely on SMIC for fabrication. SMIC’s most advanced production technology is widely understood to be a 7nm class process achieved without EUV lithography. Yield rates are low, and costs are high, and whether SMIC can scale beyond that node remains uncertain.

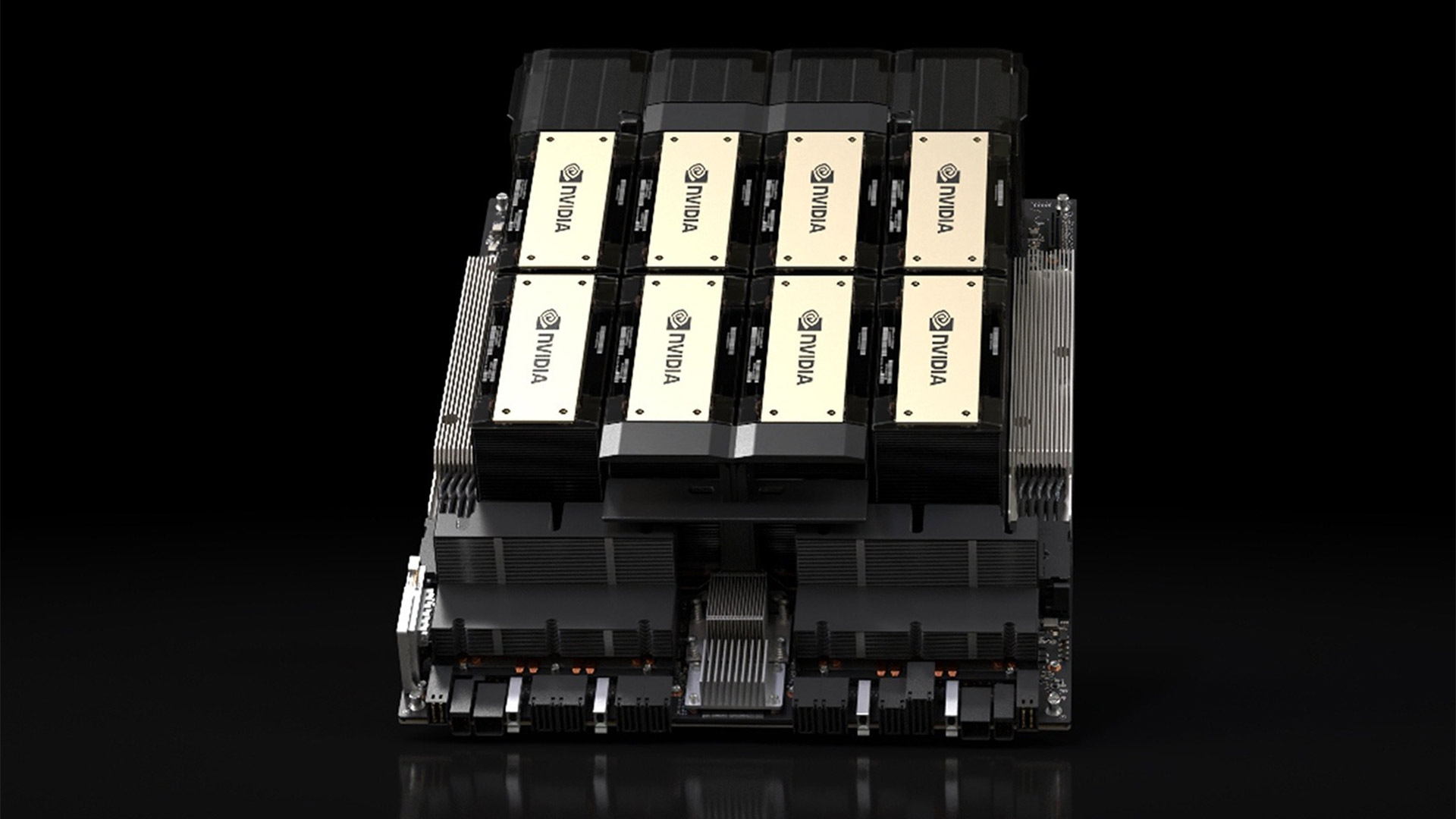

Nvidia, by contrast, continues to use TSMC’s leading-edge processes and advanced packaging. Its latest accelerators pair large compute dies with massive pools of HBM using CoWoS interposers. That combination is critical for today’s AI workloads, where memory bandwidth and capacity ultimately dictate how the GPUs perform in deployment.

Huawei’s Ascend chips simply cannot match that memory subsystem. Without access to large volumes of HBM and advanced packaging capacity, Ascend accelerators rely on slower memory configurations that bottleneck performance, particularly for LLMs. Even Huawei’s own roadmap highlights the issue, admitting that next year’s Ascend 950PR and 950DT both have lower total processing performance than the Ascend 910C.

According to projections cited in the CFR report, Huawei’s next-gen Ascend chips would at best approach H100-class performance around 2026 or 2027. By then, Nvidia will be multiple product cycles ahead. The report estimates that by 2027, the best U.S. AI chips could be more than 17 times more powerful than Huawei’s top offerings.

Manufacturing scale choke points

Performance gaps in isolation don’t paint a complete picture, though. Dominance in AI is as much about volume as throughput, and on this front, Huawei’s position appears even more untenable.

Nvidia ships AI accelerators by the millions each year, with an annual output of 3.76 million and a 98% revenue share in 2023. These chips are supported by a mature global supply chain that includes advanced memory suppliers, packaging houses, and system integrators.

Meanwhile, Huawei’s production scale is constrained at every step. SMIC’s limited yields cap the number of usable dies, and U.S. export controls on advanced memory further restrict Huawei’s ability to assemble complete accelerators, even when compute dies are available. The CFR analysis, citing figures from SemiAnalysis, estimates that Huawei may be able to produce only a few hundred thousand high-end AI chips annually under optimistic assumptions, with a figure of 200,000 to 300,000 in 2025.

Even if Huawei were to double its output year over year, it would still trail Nvidia’s installed base by a wide margin. When aggregate compute capacity is considered, rather than single-chip performance, Huawei’s position deteriorates further, with the report estimating that Huawei’s total AI compute capacity will amount to only 2% of Nvidia’s through the second half of the decade. “It is virtually impossible for Huawei to close this gap: even a hundredfold increase in AI chip production by 2027 would not even bring Huawei to half of Nvidia’s output,” the report says.

Ultimately, large-scale AI development is driven not by isolated accelerators but by clusters, and Nvidia’s strength lies not only in GPUs but also in its ability to deliver tightly integrated systems with high-speed interconnects and mature software support. Huawei can assemble clusters of Ascend chips, but at a far smaller scale and with lower efficiency. Chinese cloud providers have borne the brunt of this gap, with several having acknowledged that their biggest constraint in deploying large AI models is a lack of access to sufficient hardware. That bottleneck persists despite years of investment and aggressive state support.

Export control fears may be overstated

The CFR report goes against speculation that the recent decision to loosen U.S. export restrictions was driven, in part, by Huawei representing an imminent threat to Nvidia’s dominance in AI hardware.

While Huawei has made some progress under pressures imposed by said export restrictions, particularly in designing workable accelerators without Western fabrication partners, that has its limits. Without EUV lithography, advanced packaging capacity, and unrestricted access to HBM, Huawei’s chips remain fundamentally constrained.

Relaxing export controls in response to fears of Huawei catching up risks is fundamentally misreading the situation. Allowing additional shipments of advanced Nvidia accelerators into China may generate short-term revenue and preserve some market leverage, but it does little to alter the underlying competitive balance between the two companies; Nvidia’s lead is rooted in manufacturing depth and ecosystem maturity, not merely in product availability.

The U.S. and its allies also control key choke points in advanced semiconductor manufacturing. China’s efforts to bypass those choke points have produced some incremental gains, but nothing close to any breakthroughs that would suggest the scales tipping in Huawei’s favor — or any other Chinese firm for that matter.

The CFR’s analysis makes clear that U.S. and allied export controls on advanced chipmaking equipment and high-end AI accelerators continue to constrain China’s ability to produce competitive AI hardware at scale, thereby forcing domestic production onto less advanced nodes and slowing aggregate AI compute capacity growth relative to U.S. producers.

However, none of this implies that China’s AI ambitions should be dismissed entirely. Huawei will continue to improve its designs, and SMIC will continue to push its process technology as far as possible. But improvement is not the same as parity. Based on current trajectories, Huawei is running uphill against a competitor that is leaving it in the dust.

13 hours ago

19

13 hours ago

19

English (US) ·

English (US) ·