Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

Forward-looking: As the world faces a data tsunami, with most information destined for long-term storage, one technology could offer a sustainable, low-maintenance alternative. Whether Cerabyte can deliver on its promise of millennia-long durability and ultra-low costs remains to be seen. Still, its boiling and baking tests have already raised the bar in the race for the future of data storage.

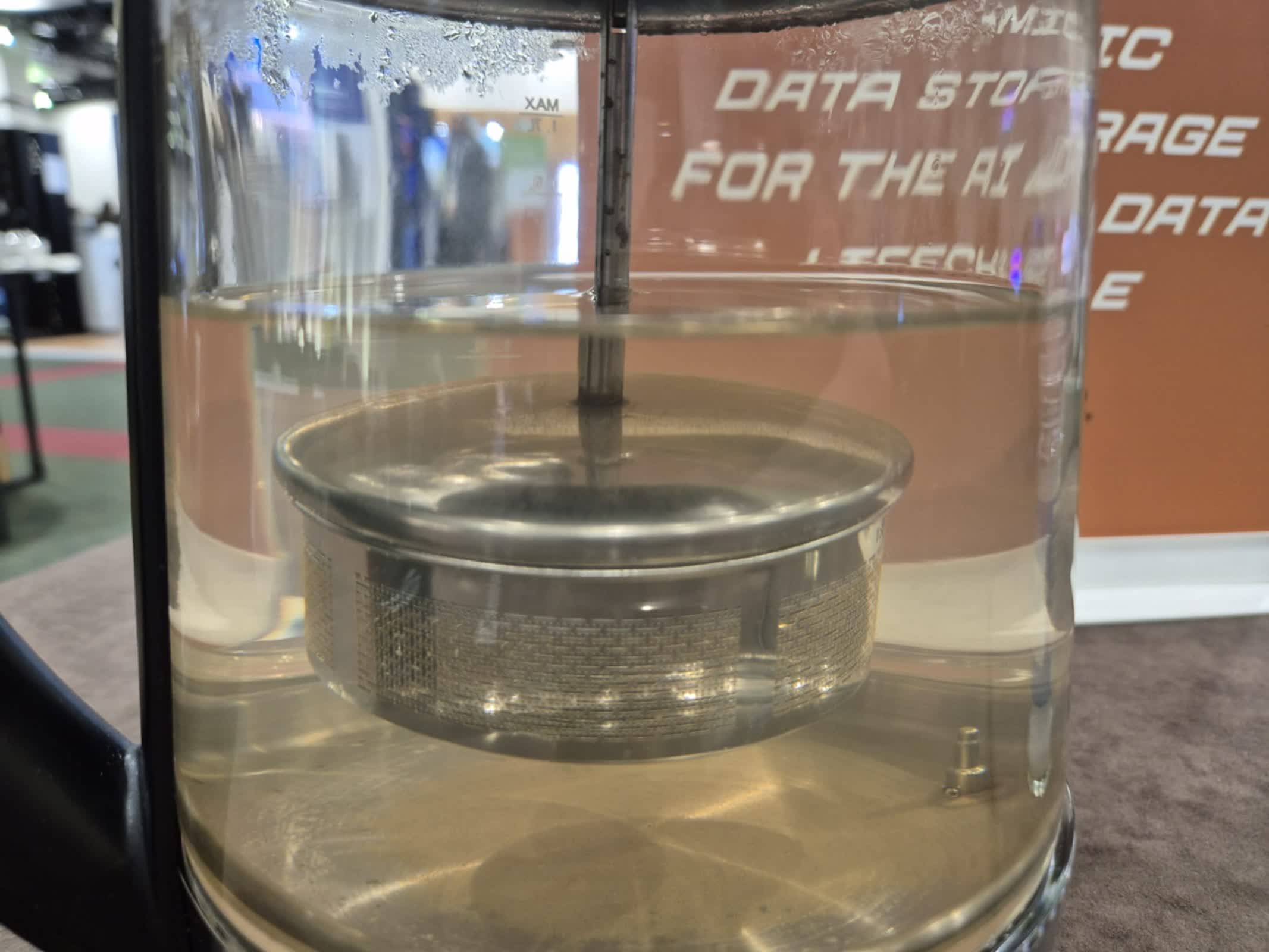

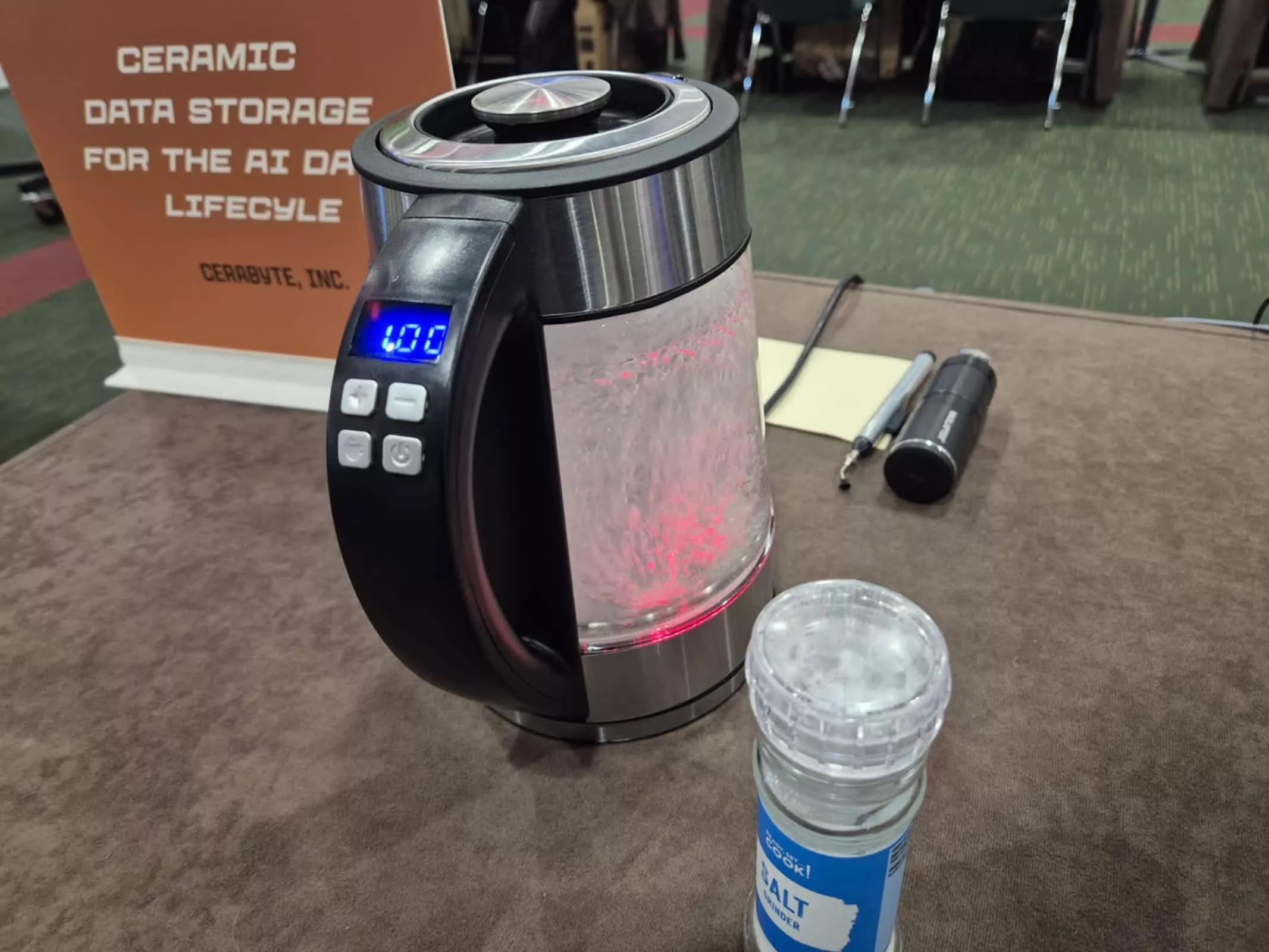

Cerabyte recently conducted an experiment that seemed more like a culinary exercise than a technology showcase. The German storage startup plunged a sliver of its archival glass storage into a kettle of boiling salt water, then roasted it in a pizza oven.

Despite enduring temperatures of 100°C in the kettle and 250°C in the oven, the storage medium emerged unscathed, with its data fully intact. This experiment – along with a similar live demonstration at the Open Compute Project Summit in Dublin – was not just a spectacle. It was Cerabyte's way of proving a bold claim: its storage media can withstand conditions that would destroy conventional data storage.

After 24 hours, the kettle starts to corrode.

Founded in 2022, Cerabyte is on a mission to upend the world of digital archiving. The company's technology relies on an ultra-thin ceramic layer – just 50 to 100 atoms thick – applied to a glass substrate.

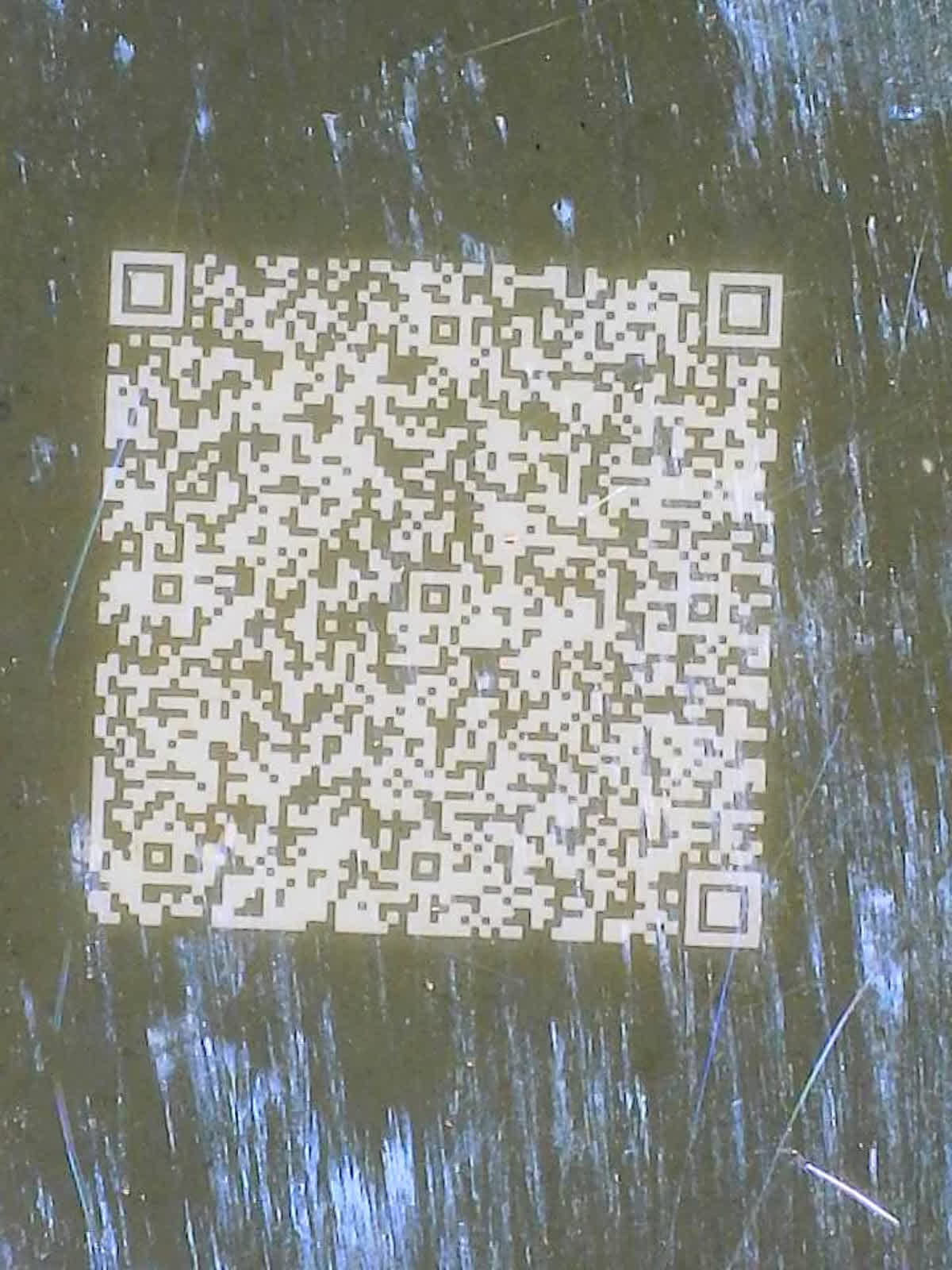

Using femtosecond lasers, data is etched into the ceramic in nanoscale holes. Each 9 cm² chip can store up to 1 GB of information per side, written at a rate of two million bits per laser pulse. Cerabyte claims the result is a medium as durable as ancient hieroglyphs, with a projected lifespan of 5,000 years or more.

The kettle boils the salt water for two days.

The durability of glass is well known. Its resistance to aging, fire, water, radiation, and even electromagnetic pulses makes it a natural candidate for "cold storage." Cerabyte's tests – including boiling the media in salt water for days (long enough to corrode the kettle itself) and baking it at high heat – were designed to underscore this resilience.

While the company has not disclosed how the ceramic layer or its bond to the glass would fare under physical shock, the media's resistance to environmental hazards is clear.

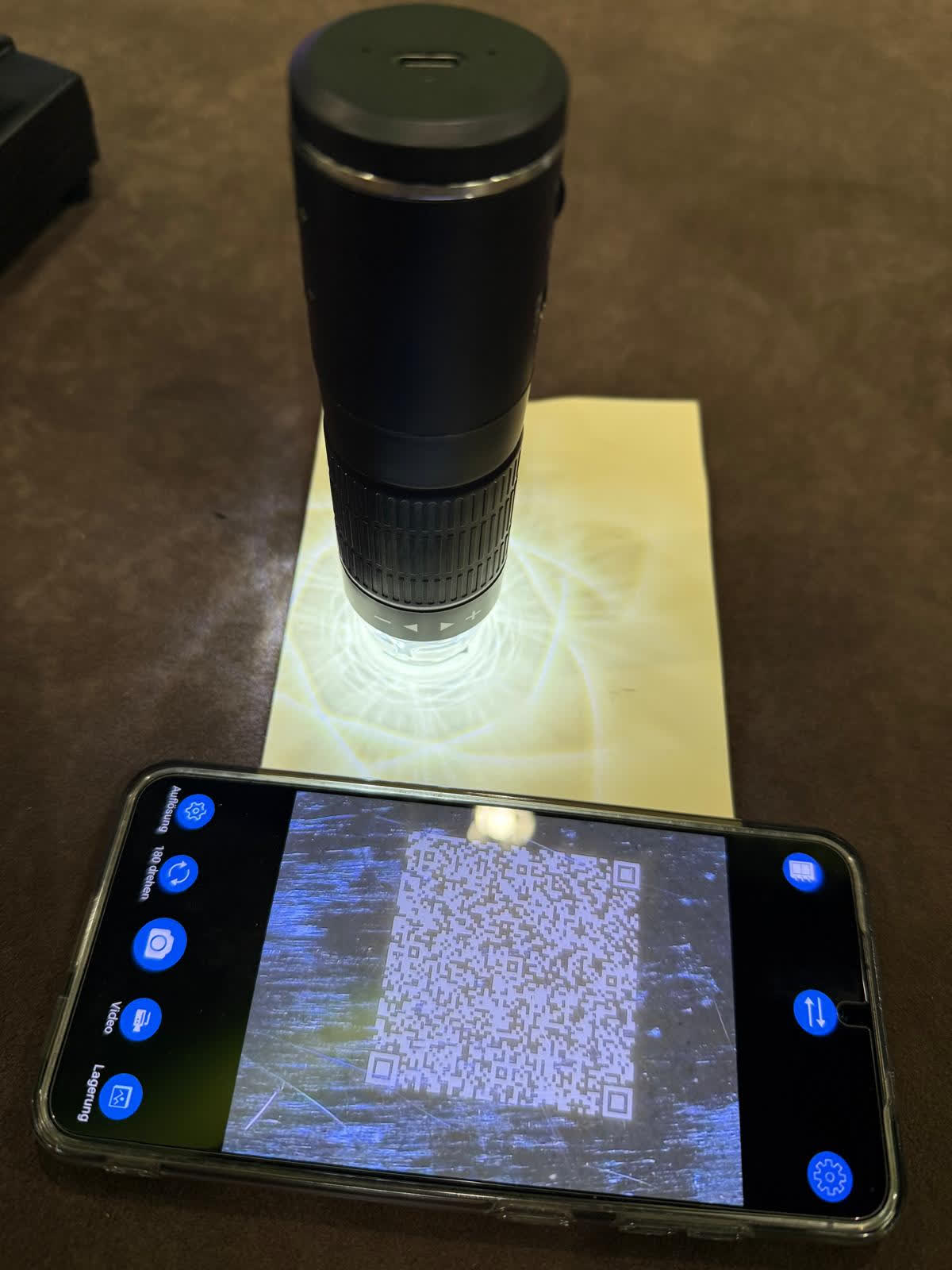

The storage device is still readable.

Cerabyte's ambitions extend beyond durability. The startup aims to reduce the cost of archival storage to less than $1 per terabyte by 2030 – a target that could transform the economics of long-term data retention.

Then it spends six hours between 90 and 100°C.

The company's roadmap includes glass slides and CeraTape, a tape format with exabyte-scale capacity designed to integrate with existing robotic library systems.

After cleaning the device with freshwater, it is put under the microscope.

Cerabyte's demonstrations have drawn attention at industry events, where the ability to retrieve data after extreme stress tests has impressed observers.

Unlike other archival methods – magnetic tape, hard drives, or even optical discs, all of which degrade over decades – Cerabyte's ceramic-on-glass approach promises to eliminate the need for regular data migration or or energy-hungry maintenance.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·