Serving tech enthusiasts for over 25 years.

TechSpot means tech analysis and advice you can trust.

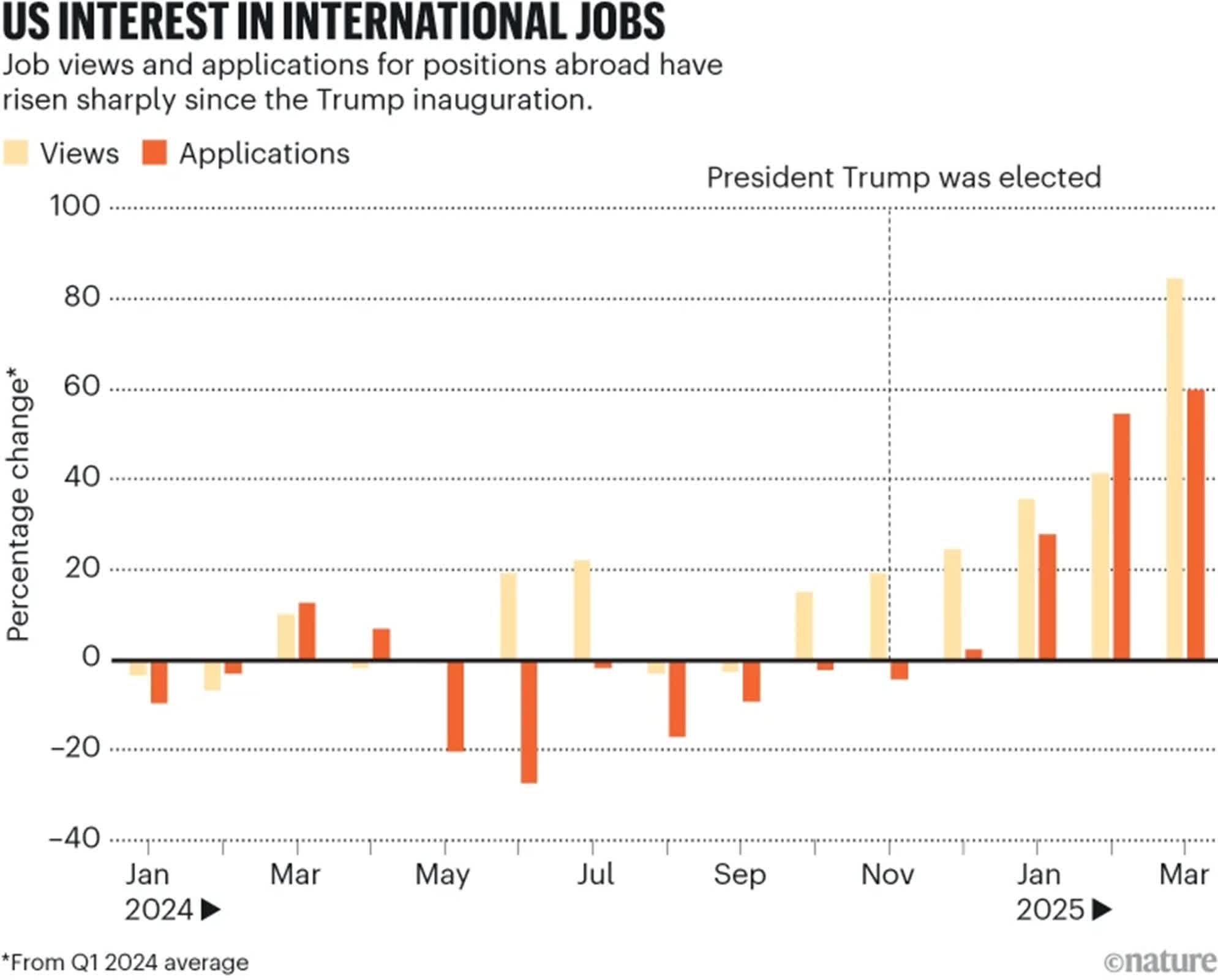

The big picture: A growing number of American researchers are exploring scientific careers outside the United States, spurred by deep funding reductions and political interference that have upended the nation's research environment. Recent figures from Nature's global science jobs platform highlight this trend: in the first quarter of 2025, applications from US-based scientists for overseas positions climbed by 32 percent compared to a year earlier. Meanwhile, the number of American users searching for international roles increased by 35 percent, and March alone saw a 68 percent year-over-year spike in views of non-US job postings.

The exodus is largely driven by abrupt federal funding withdrawals and project cancellations. Last month, over 200 grants supporting HIV and AIDS research were terminated. The National Institutes of Health also cut back on Covid-19 research funding and eliminated $400 million in research grants at Columbia University, citing campus unrest related to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

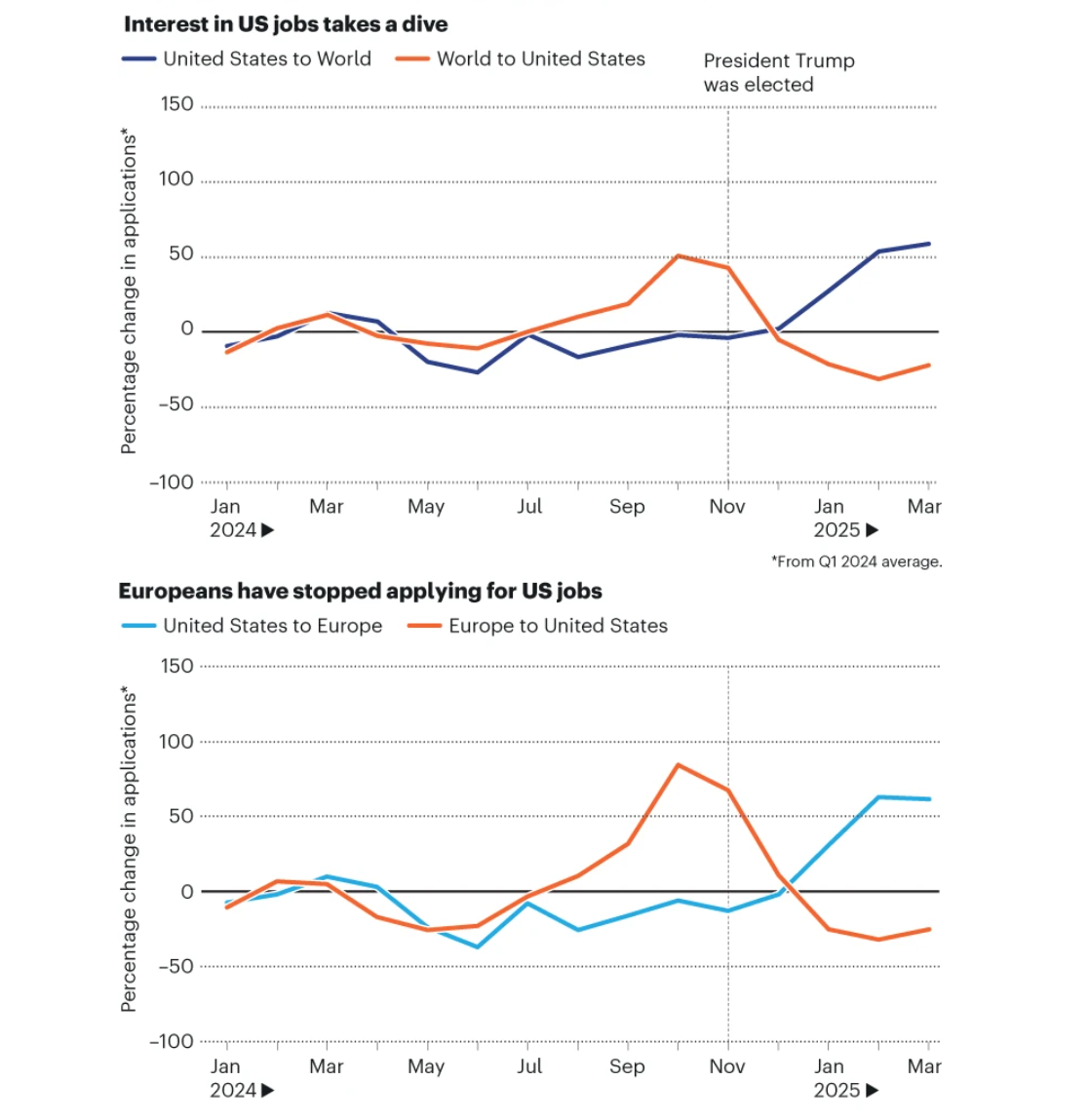

These changes have sent shockwaves through the research community. James Richards, head of Global Talent Solutions at Springer Nature, which operates the Nature Careers jobs board, described the current situation as unparalleled: "To see this big drop in views and applications to the US – and the similar rise in those looking to leave – is unprecedented," he told Nature.

A separate Nature poll found that 75 percent of US researchers surveyed are contemplating leaving the country. The shift is especially notable in Canada, where applications from American scientists rose by 41 percent in early 2025, while Canadian interest in US positions fell by 13 percent.

For individual scientists, the instability is personal. Chemical engineer Valerie Niemann, who previously worked at Stanford University, recently accepted a postdoctoral role at the University of Bern in Switzerland. "People don't know how long their postdocs will be," she told the publication. "We can't apply for fellowships because we don't know how long they're going to exist."

Universities in Europe are taking steps to accommodate displaced researchers. In March, Aix-Marseille University in France launched the Safe Place for Science initiative, dedicating €15 million to support scholars in climate, health, and environmental fields – especially those affected by US policy changes.

Within its first month, the program received 298 applications, 70 percent from US scientists. "What's happening is terrible for American research," said university president Éric Berton. "We felt it was our duty to do what we could to show scientists there was a little light in the south of France where they could do their research, be a lot freer and where they were wanted."

Interest in European opportunities is rising sharply: US applications to European jobs on the Nature Careers board increased by 32 percent in March, while European applications to US roles declined by 41 percent.

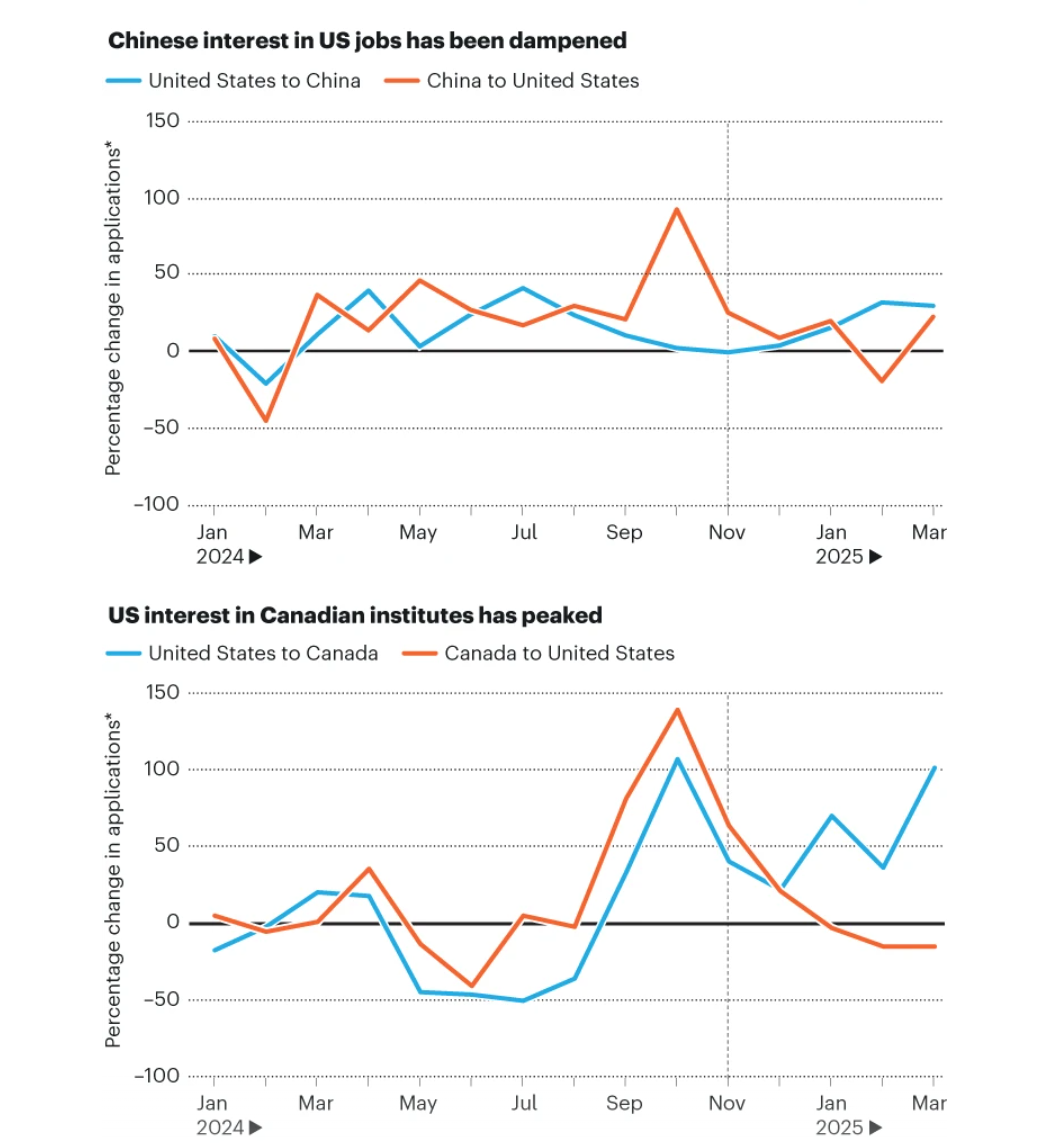

Germany's Max Planck Society also reports heightened interest from American researchers and a surge in applications from Asia. Spokesperson Christina Beck attributes this to scientists "possibly reorienting themselves and preferring Europe to the US."

The Society recently introduced a Transatlantic Program to establish joint research centers with US partners and create new positions for junior and senior scientists who can no longer work in the United States.

The migration trend isn't limited to Europe, however. Chinese recruiters are actively targeting US scientists, and American interest in research jobs in China rose by 30 percent in views and 20 percent in applications in early 2025. Other Asian countries are also seeing increased attention from US-based researchers.

The shifting landscape is affecting morale among American scientists. Michael Friedlander, director of the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech, notes that more graduate students and postdocs are questioning their future in science.

A February survey by the National Postdoctoral Association revealed that 43 percent of respondents felt their jobs were at risk, 35 percent reported delays or threats to their research, and 9 percent said they could not speak freely at work.

As more US scientists consider relocating, Niemann's decision to move abroad is emblematic of their difficult choices as the US research environment becomes increasingly unstable.

"It's a good time to move on, given the political climate," she said, adding that many of her colleagues share her sentiment. The United States, once a global magnet for scientific talent, now faces an uncertain future as researchers weigh their options in a rapidly changing world.

Image credit: Nature

English (US) ·

English (US) ·